Getting started with HTML

In this article we cover the absolute basics of HTML. To get you started, this article defines elements, attributes, and all the other important terms you may have heard. It also explains where these fit into HTML. You will learn how HTML elements are structured, how a typical HTML page is structured, and other important basic language features. Along the way, there will be an opportunity to play with HTML too!

| Prerequisites: | Basic computer literacy, basic software installed, and basic knowledge of working with files. |

|---|---|

| Objective: | To gain basic familiarity with HTML, and practice writing a few HTML elements. |

What is HTML?

HTML (Hypertext Markup Language) is a markup language that tells web browsers how to structure the web pages you visit. It can be as complicated or as simple as the web developer wants it to be. HTML consists of a series of elements, which you use to enclose, wrap, or mark up different parts of content to make it appear or act in a certain way. The enclosing tags can make content into a hyperlink to connect to another page, italicize words, and so on. For example, consider the following line of text:

My cat is very grumpy

If we wanted the text to stand by itself, we could specify that it is a paragraph by enclosing it in a paragraph (<p>) element:

<p>My cat is very grumpy</p>

Note: Tags in HTML are not case-sensitive. This means they can be written in uppercase or lowercase. For example, a <title> tag could be written as <title>, <TITLE>, <Title>, <TiTlE>, etc., and it will work. However, it is best practice to write all tags in lowercase for consistency and readability.

Anatomy of an HTML element

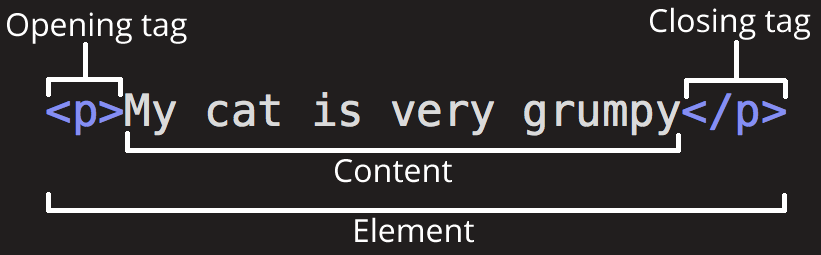

Let's further explore our paragraph element from the previous section:

The anatomy of our element is:

- The opening tag: This consists of the name of the element (in this example, p for paragraph), wrapped in opening and closing angle brackets. This opening tag marks where the element begins or starts to take effect. In this example, it precedes the start of the paragraph text.

- The content: This is the content of the element. In this example, it is the paragraph text.

- The closing tag: This is the same as the opening tag, except that it includes a forward slash before the element name. This marks where the element ends. Failing to include a closing tag is a common beginner error that can produce peculiar results.

The element is the opening tag, followed by content, followed by the closing tag.

Active learning: creating your first HTML element

Edit the line below in the "Editable code" area by wrapping it with the tags <em> and </em>. To open the element, put the opening tag <em> at the start of the line. To close the element, put the closing tag </em> at the end of the line. Doing this should give the line italic text formatting! See your changes update live in the Output area.

If you make a mistake, you can clear your work using the Reset button. If you get really stuck, press the Show solution button to see the answer.

Nesting elements

Elements can be placed within other elements. This is called nesting. If we wanted to state that our cat is very grumpy, we could wrap the word very in a <strong> element, which means that the word is to have strong(er) text formatting:

<p>My cat is <strong>very</strong> grumpy.</p>

There is a right and wrong way to do nesting. In the example above, we opened the p element first, then opened the strong element. For proper nesting, we should close the strong element first, before closing the p.

The following is an example of the wrong way to do nesting:

<p>My cat is <strong>very grumpy.</p></strong>

The tags have to open and close in a way that they are inside or outside one another. With the kind of overlap in the example above, the browser has to guess at your intent. This kind of guessing can result in unexpected results.

Block versus inline elements

There are two important categories of elements to know in HTML: block-level elements and inline elements.

- Block-level elements form a visible block on a page. A block-level element appears on a new line following the content that precedes it. Any content that follows a block-level element also appears on a new line. Block-level elements are usually structural elements on the page. For example, a block-level element might represent headings, paragraphs, lists, navigation menus, or footers. A block-level element wouldn't be nested inside an inline element, but it might be nested inside another block-level element.

- Inline elements are contained within block-level elements, and surround only small parts of the document's content (not entire paragraphs or groupings of content). An inline element will not cause a new line to appear in the document. It is typically used with text, for example an

<a>element creates a hyperlink, and elements such as<em>or<strong>create emphasis.

Consider the following example:

<em>first</em><em>second</em><em>third</em>

<p>fourth</p><p>fifth</p><p>sixth</p>

<em> is an inline element. As you see below, the first three elements sit on the same line, with no space in between. On the other hand, <p> is a block-level element. Each p element appears on a new line, with space above and below. (The spacing is due to default CSS styling that the browser applies to paragraphs.)

Note: HTML5 redefined the element categories: see Element content categories. While these definitions are more accurate and less ambiguous than their predecessors, the new definitions are a lot more complicated to understand than block and inline. This article will stay with these two terms.

Note: The terms block and inline, as used in this article, should not be confused with the types of CSS boxes that have the same names. While the names correlate by default, changing the CSS display type doesn't change the category of the element, and doesn't affect which elements it can contain and which elements it can be contained in. One reason HTML5 dropped these terms was to prevent this rather common confusion.

Note: Find useful reference pages that include lists of block and inline elements. See Block-level elements and Inline elements.

Empty elements

Not all elements follow the pattern of an opening tag, content, and a closing tag. Some elements consist of a single tag, which is typically used to insert/embed something in the document. For example, the <img> element embeds an image file onto a page:

<img src="https://raw.githubusercontent.com/mdn/beginner-html-site/gh-pages/images/firefox-icon.png">

This would output the following:

Note: Empty elements are sometimes called void elements.

Note: In HTML, there is no requirement to add a / at the end of an empty element's tag, for example: <img src="images/cat.jpg" alt="cat" />. However, it is also a valid syntax and you may do this when you want your HTML to be valid XML.

Attributes

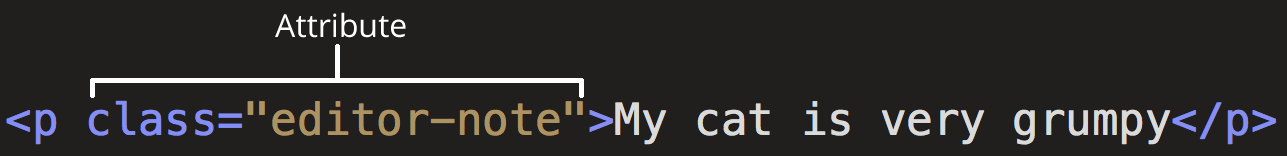

Elements can also have attributes. Attributes look like this:

Attributes contain extra information about the element that won't appear in the content. In this example, the class attribute is an identifying name used to target the element with style information.

An attribute should have:

- A space between it and the element name. (For an element with more than one attribute, the attributes should be separated by spaces too.)

- The attribute name, followed by an equal sign.

- An attribute value, wrapped with opening and closing quote marks.

Active learning: Adding attributes to an element

Another example of an element is <a>. This stands for anchor. An anchor can make the text it encloses into a hyperlink. Anchors can take a number of attributes, but several are as follows:

href: This attribute's value specifies the web address for the link. For example:href="https://www.mozilla.org/".title: Thetitleattribute specifies extra information about the link, such as a description of the page that is being linked to. For example,title="The Mozilla homepage". This appears as a tooltip when a cursor hovers over the element.target: Thetargetattribute specifies the browsing context used to display the link. For example,target="_blank"will display the link in a new tab. If you want to display the linked content in the current tab, just omit this attribute.

Edit the line below in the Input area to turn it into a link to your favorite website.

- Add the

<a>element. - Add the

hrefattribute and thetitleattribute. - Specify the

targetattribute to open the link in the new tab.

You will be able to see your changes update live in the Output area. You should see a link—that when hovered over—displays the value of the title attribute, and when clicked, navigates to the web address in the href attribute. Remember that you need to include a space between the element name, and between each attribute.

If you make a mistake, you can always reset it using the Reset button. If you get really stuck, press the Show solution button to see the answer.

Boolean attributes

Sometimes you will see attributes written without values. This is entirely acceptable. These are called Boolean attributes. Boolean attributes can only have one value, which is generally the same as the attribute name. For example, consider the disabled attribute, which you can assign to form input elements. (You use this to disable the form input elements so the user can't make entries. The disabled elements typically have a grayed-out appearance.) For example:

<input type="text" disabled="disabled">

As shorthand, it is acceptable to write this as follows:

<!-- using the disabled attribute prevents the end user from entering text into the input box -->

<input type="text" disabled>

<!-- text input is allowed, as it doesn't contain the disabled attribute -->

<input type="text">

For reference, the example above also includes a non-disabled form input element.The HTML from the example above produces this result:

Omitting quotes around attribute values

If you look at code for a lot of other sites, you might come across a number of strange markup styles, including attribute values without quotes. This is permitted in certain circumstances, but it can also break your markup in other circumstances. For example, if we revisit our link example from earlier, we could write a basic version with only the href attribute, like this:

<a href=https://www.mozilla.org/>favorite website</a>

However, as soon as we add the title attribute in this way, there are problems:

<a href=https://www.mozilla.org/ title=The Mozilla homepage>favorite website</a>

As written above, the browser misinterprets the markup, mistaking the title attribute for three attributes: a title attribute with the value The, and two Boolean attributes, Mozilla and homepage. Obviously, this is not intended! It will cause errors or unexpected behavior, as you can see in the live example below. Try hovering over the link to view the title text!

Always include the attribute quotes. It avoids such problems, and results in more readable code.

Single or double quotes?

In this article you will also notice that the attributes are wrapped in double quotes. However, you might see single quotes in some HTML code. This is a matter of style. You can feel free to choose which one you prefer. Both of these lines are equivalent:

<a href="https://www.example.com">A link to my example.</a>

<a href='https://www.example.com'>A link to my example.</a>

Make sure you don't mix single quotes and double quotes. This example (below) shows a kind of mixing quotes that will go wrong:

<a href="https://www.example.com'>A link to my example.</a>

However, if you use one type of quote, you can include the other type of quote inside your attribute values:

<a href="https://www.example.com" title="Isn't this fun?">A link to my example.</a>

To use quote marks inside other quote marks of the same type (single quote or double quote), use HTML entities. For example, this will break:

<a href='https://www.example.com' title='Isn't this fun?'>A link to my example.</a>

Instead, you need to do this:

<a href='https://www.example.com' title='Isn't this fun?'>A link to my example.</a>

Anatomy of an HTML document

Individual HTML elements aren't very useful on their own. Next, let's examine how individual elements combine to form an entire HTML page:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<title>My test page</title>

</head>

<body>

<p>This is my page</p>

</body>

</html>

Here we have:

<!DOCTYPE html>: The doctype. When HTML was young (1991-1992), doctypes were meant to act as links to a set of rules that the HTML page had to follow to be considered good HTML. Doctypes used to look something like this:More recently, the doctype is a historical artifact that needs to be included for everything else to work right.<!DOCTYPE html PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD XHTML 1.0 Transitional//EN" "http://www.w3.org/TR/xhtml1/DTD/xhtml1-transitional.dtd"><!DOCTYPE html>is the shortest string of characters that counts as a valid doctype. That is all you need to know!<html></html>: The<html>element. This element wraps all the content on the page. It is sometimes known as the root element.<head></head>: The<head>element. This element acts as a container for everything you want to include on the HTML page, that isn't the content the page will show to viewers. This includes keywords and a page description that would appear in search results, CSS to style content, character set declarations, and more. You will learn more about this in the next article of the series.<meta charset="utf-8">: The<meta>element. This element represents metadata that cannot be represented by other HTML meta-related elements, like<base>,<link>,<script>,<style>or<title>. Thecharsetattributes sets the character set for your document to UTF-8, which includes most characters from the vast majority of human written languages. With this setting, the page can now handle any textual content it might contain. There is no reason not to set this, and it can help avoid some problems later.<title></title>: The<title>element. This sets the title of the page, which is the title that appears in the browser tab the page is loaded in. The page title is also used to describe the page when it is bookmarked.<body></body>: The<body>element. This contains all the content that displays on the page, including text, images, videos, games, playable audio tracks, or whatever else.

Active learning: Adding some features to an HTML document

If you want to experiment with writing some HTML on your local computer, you can:

- Copy the HTML page example listed above.

- Create a new file in your text editor.

- Paste the code into the new text file.

- Save the file as

index.html.

Note: You can also find this basic HTML template on the MDN Learning Area GitHub repo.

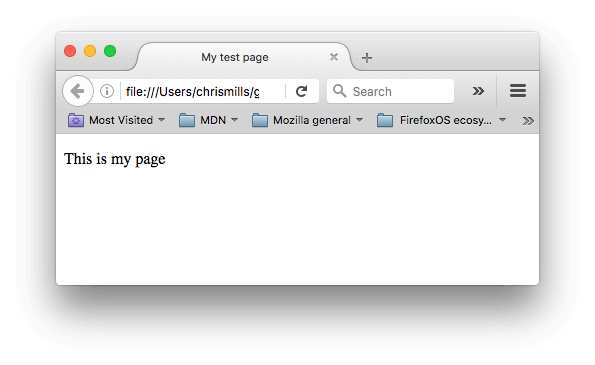

You can now open this file in a web browser to see what the rendered code looks like. Edit the code and refresh the browser to see what the result is. Initially the page looks like this:

In this exercise, you can edit the code locally on your computer, as described previously, or you can edit it in the sample window below (the editable sample window represents just the contents of the

In this exercise, you can edit the code locally on your computer, as described previously, or you can edit it in the sample window below (the editable sample window represents just the contents of the <body> element, in this case). Sharpen your skills by implementing the following tasks:

- Just below the opening tag of the

<body>element, add a main title for the document. This should be wrapped inside an<h1>opening tag and</h1>closing tag. - Edit the paragraph content to include text about a topic that you find interesting.

- Make important words stand out in bold by wrapping them inside a

<strong>opening tag and</strong>closing tag. - Add a link to your paragraph, as explained earlier in the article.

- Add an image to your document. Place it below the paragraph, as explained earlier in the article. Earn bonus points if you manage to link to a different image (either locally on your computer, or somewhere else on the web).

If you make a mistake, you can always reset it using the Reset button. If you get really stuck, press the Show solution button to see the answer.

Whitespace in HTML

In the examples above, you may have noticed that a lot of whitespace is included in the code. This is optional. These two code snippets are equivalent:

<p>Dogs are silly.</p>

<p>Dogs are

silly.</p>

No matter how much whitespace you use inside HTML element content (which can include one or more space character, but also line breaks), the HTML parser reduces each sequence of whitespace to a single space when rendering the code. So why use so much whitespace? The answer is readability.

It can be easier to understand what is going on in your code if you have it nicely formatted. In our HTML we've got each nested element indented by two spaces more than the one it is sitting inside. It is up to you to choose the style of formatting (how many spaces for each level of indentation, for example), but you should consider formatting it.

Entity references: Including special characters in HTML

In HTML, the characters <, >,",' and & are special characters. They are parts of the HTML syntax itself. So how do you include one of these special characters in your text? For example, if you want to use an ampersand or less-than sign, and not have it interpreted as code.

You do this with character references. These are special codes that represent characters, to be used in these exact circumstances. Each character reference starts with an ampersand (&), and ends with a semicolon (;).

| Literal character | Character reference equivalent |

|---|---|

| < | < |

| > | > |

| " | " |

| ' | ' |

| & | & |

The character reference equivalent could be easily remembered because the text it uses can be seen as less than for '<' , quotation for ' " ' and similarly for others. To find more about entity reference, see List of XML and HTML character entity references (Wikipedia).

In the example below, there are two paragraphs:

<p>In HTML, you define a paragraph using the <p> element.</p>

<p>In HTML, you define a paragraph using the <p> element.</p>

In the live output below, you can see that the first paragraph has gone wrong. The browser interprets the second instance of <p> as starting a new paragraph. The second paragraph looks fine because it has angle brackets with character references.

Note: You don't need to use entity references for any other symbols, as modern browsers will handle the actual symbols just fine as long as your HTML's character encoding is set to UTF-8.

HTML comments

HTML has a mechanism to write comments in the code. Browsers ignore comments, effectively making comments invisible to the user. The purpose of comments is to allow you to include notes in the code to explain your logic or coding. This is very useful if you return to a code base after being away for long enough that you don't completely remember it. Likewise, comments are invaluable as different people are making changes and updates.

To write an HTML comment, wrap it in the special markers <!-- and -->. For example:

<p>I'm not inside a comment</p>

<!-- <p>I am!</p> -->

As you can see below, only the first paragraph is displayed in the live output.

Summary

You made it to the end of the article! We hope you enjoyed your tour of the basics of HTML.

At this point, you should understand what HTML looks like, and how it works at a basic level. You should also be able to write a few elements and attributes. The subsequent articles of this module go further on some of the topics introduced here, as well as presenting other concepts of the language.

Note: As you start to learn more about HTML, consider learning the basics of Cascading Style Sheets, or CSS. CSS is the language used to style web pages: for example, changing fonts or colors, or altering the page layout. HTML and CSS work well together, as you will soon discover.